A long answer follows, but it’s reasonably complete.

Biggs might have overstated it a little with the word “nightmare,” but it will be a problem.

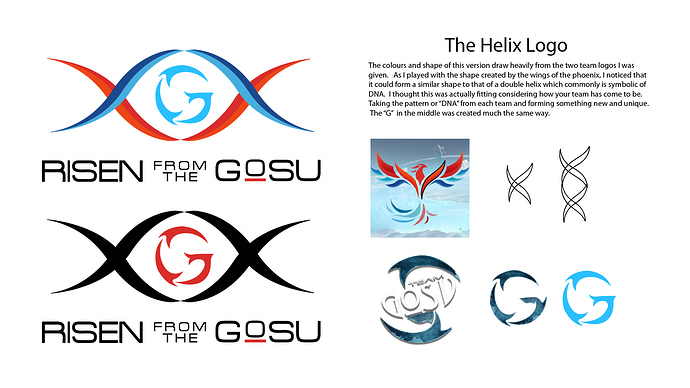

You might know what Pantone (or spot) colors are, but assuming you don’t, they’re (in this context) printing inks that come in specific colors. Unlike 4-color process (CMYK), the colors in a spot color job aren’t mixed on the press with various dot densities of the 4 process inks. Instead, every color is printed separately with a Pantone ink, and each one of those colors costs extra money and requires a more expensive multi-colored press to print it.

This provides pure, rich, vibrant colors that can’t be easily achieved with standard CMYK printing. The equivalent of spot colors are also used in those instances where something can’t be run through a traditional printing press, like an embroidered hat or a screen printed jersey.

So let’s say the team wanted to screen print a few dozen t-shirts. Your design, because of all the colors, would require five separate screens be burned, five different inks be obtained, and five separate squeegee pulls on each shirt. You would need one each for the dark blue, the light blue, the dark red, the light red and the black. And if you printed it on a dark colored shirt, a sixth white ink might be needed beneath it all. There are ways around this, like using screen tints to lighten the dark blue, but it comes at a visual quality cost. And all these colors come with a monetary cost too since they involve extra work.

So on to registration…

When solid colors that abut each other are printed using spot colors (like with screen or offset printing) the registration of those colors has to be exact. If the registration is off, even by the width of a hair or two, a white line will appear between the two colors or, if the registration is off the other direction, a hairline of one color being printed on top of the other, which will create a mixture of those two colors.

Normally, printers mitigate this problem by trapping and spreading. These terms refer to pulling in or out the edge of the printed area just enough to ensure there’s no white gap between them. If, for example, blue is trapped by a millimeter into a black area, nobody will ever notice. However, in your logo, there’s really no good way to trap the red into the blue since the combination will produce a purple line. In other words, unless the printing registration is perfect, when printed with spot colors, this logo will likely be plagued with small white lines between the colors or small purple lines where the blue overlaps the red. This purple overlap trap combination color won’t be as problematic with screen printing since the inks are opaque, but with offset, it’ll be an issue since the inks are transparent.

Printers deal with this stuff all the time and have gotten good at working around these kinds of things. It does, however, present problems that can be best avoided by taking them into consideration during the design process.

For online use or CMYK printing or digital printing, these things aren’t so much of a concern. For an online team, like you described, none of these things are likely huge concerns. If you were designing a logo for a big company, however, these problems would likely force a logo redo as soon as it became apparent that this general problem kept rearing its head and costing money and hampering quality each time it did.

Thank you for all your efforts!

Thank you for all your efforts!

The negative space with the current G, makes me think of a turkey?

The negative space with the current G, makes me think of a turkey?