I’ve always been mystified by seemingly intelligent clients who insist on counterproductive design solutions. Instead of deferring to the talents and wisdom of experienced designers, they regard designers as hired hands to implement their bad ideas.

I had always attributed this to a combination of ignorance and narcissism. But many of these clients and employers are neither stupid nor especially narcissistic, so I always felt there must be a more complete explanation.

Recently, I stumbled across a psychological phenomenon called the Dunning-Kruger effect, which might explain some of what I’ve been missing. It’s a well-researched and studied concept developed by two Cornell University psychologists.

Here’s a link to one of many articles about it: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/dunning-kruger-effect

I’m paraphrasing, but in essence, many people who know only a little about something do not yet know enough about the subject to grasp the extent of their ignorance. Their rudimentary knowledge gives them unwarranted confidence in subjects that are beyond their current understanding. Sadly, it’s this ignorance that prevents them from being able to recognize their ignorance, which sets the stage for them confidently making bad decisions while discounting experienced experts who could have prevented it.

Quoting from the article, “Those with limited knowledge in a domain suffer a dual burden: Not only do they reach mistaken conclusions and make regrettable errors, but their incompetence robs them of the ability to realize it,”

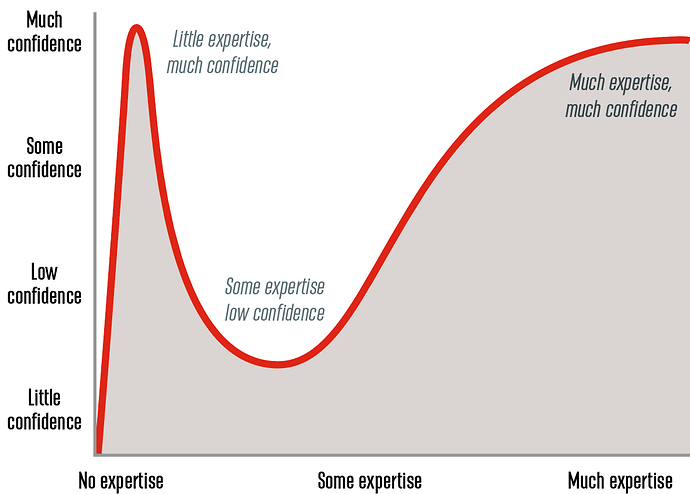

When plotted on an X-Y axis, it looks something like this:

As the graph shows, those most vulnerable to the Dunning-Kruger Effect start out with no expertise in a subject and, understandably, have no confidence in their expertise.

However, after learning just a little about a subject, their confidence skyrockets to a point where they assume themselves to be experts without realizing how much they don’t know. At this point, most of these people also assume they know enough about a subject to have no reason to pursue it further — stuck at the level of much confidence but little expertise.

The studies indicate that when prompted to learn more beyond their superficial understanding, they soon begin to realize how much they don’t know and how complex the subject is. This causes their confidence to drop almost as fast as it rose. If they stick with it long enough, they will gain experience and more realistic levels of confidence.

I haven’t yet decided how to use this information when dealing with overconfident clients and their bad design ideas. Maybe it’s a matter of designers carefully and constructively speaking about design considerations that are slightly over their clients’ heads. I’m not suggesting talking down to clients, I’m suggesting, instead, speaking to them with an air of confidence and expertise that elicits additional questions and requests for clarification. It’s in these kinds of conversations where designers can demonstrate the kind of expertise and proficiency that might cause reasonable clients to realize they’re talking to true experts whose judgment can be trusted.